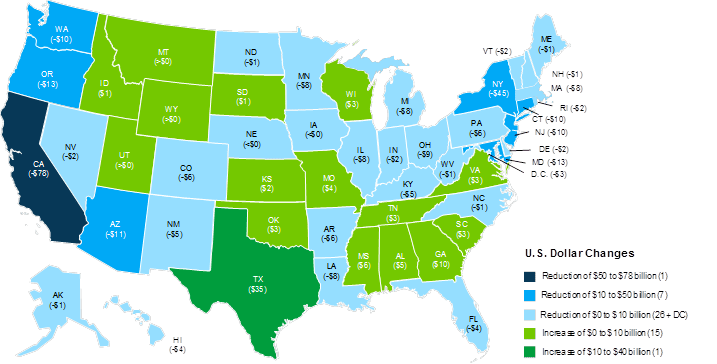

Which states could win and lose from the new ObamaCare repeal bill

The ObamaCare repeal bill set for a possible vote next week in the Senate would create winners and losers among the 50 states that would be asked to implement their own health-care plans with block grants of federal funding.

The bill, sponsored by Republican Sens. Lindsey Graham (S.C.) and Bill Cassidy (La.), ends federal funding for ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion and the subsidies that help people afford coverage, as well as the law’s insurance mandate.

Instead, states would be given pots of money and would get to decide how to spend it.

The bill redistributes money from high-spending Medicaid expansion states — like California — to states that rejected the Medicaid expansion — like Texas.

“The Graham-Cassidy bill would significantly reduce funding to states over the long term, particularly for states that have already expanded Medicaid,” said Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at Avalere, a health care consulting group in D.C. “States would have broad flexibility to shape their markets but would have less funding to subsidize coverage for low- and middle-income individuals.”

The bill would also transform the federal government’s funding of the traditional Medicaid program from an open-ended entitlement to a per-person cap, resulting in less money flowing to states. This could eventually force states to cut benefits or reduce eligibility in their programs.

Here’s a look at which states would seem to come out ahead and behind under the Graham-Cassidy proposal.

Loser — States that expanded Medicaid

ObamaCare paid for states to expand their Medicaid programs to more low-income adults, with 31 states and Washington, D.C., eventually taking up the offer.

The Medicaid expansion has been one of the main sticking points as Republicans try to repeal ObamaCare. Some moderate Republicans like what the program has done for their state and don’t want to lose the extra funds.

But the Graham-Cassidy bill would reallocate funding from states that expanded their Medicaid programs to states that didn’t.

According to a Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) analysis of the bill released on Thursday, states that expanded their programs would lose $180 billion between 2020, when the law would take effect, and 2026, when the block grants end.

This will have a large impact on expansion states with high populations such as New York and California.

A study of the bill from Avalere puts the loss at $45 billion for New York and $78 billion for California, while the KFF analysis estimates New York would lose $52 billion and California would lose $62 billion.

Graham said this week it was the goal to provide more equity between states that expanded Medicaid and ones that didn’t.

“Our goal is, by 2026, to make sure that every patient in every state gets the same contribution, roughly, from the federal government, and allow people in your state to make decisions that would have been made in Washington,” Graham told reporters Tuesday.

Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), who already said he wouldn’t support the bill because it’s not a “full repeal,” puts it more bluntly: “It just looks like the Republicans are taking the money from the Democrat states and giving it to the Republican states.”

A handful of red or purple states, like Louisiana, Arizona and Alaska would also stand to lose funding under this proposal.

Two GOP senators, John McCain (Ariz.) and Lisa Murkowski (Alaska), find themselves in a difficult position on the repeal vote because their states expanded Medicaid.

Alaska would lose about $1 billion between 2020 and 2026, according to the Avalere analysis, while Arizona would lose $11 billion. The KFF study has Arizona losing $4.4 billion within the same time period.

The GOP may need both McCain and Murkowski to vote for the Cassidy-Graham bill to get it to the House.

But there’s no guarantee the proposal can easily pass the lower chamber.

In the House, Republicans from Medicaid expansion states like New York and California may also have to make a hard choice on whether to support the bill.

Three of New York’s nine Republican congressmen — Reps. John Faso, Pete King and Tom Reed — have already voiced concerns about the bill.

“Right now, I don’t see how I could vote for it,” King told The Washington Post this week.

“It’s extremely damaging to New York.”

All three voted for the House-passed American Health Care Act in May.

Winner — States that didn’t expand Medicaid

For the most part, the 19 states that rejected ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion and decided not to take federal money to provide health care for more poor adults come out ahead under the new GOP bill.

According to the KFF analysis, nonexpansion states would get an additional $73 billion between 2020 and 2026.

This generally benefits Republican led states that opposed ObamaCare and the expansion of a federal entitlement program such as Wisconsin, Utah, Kansas and Mississippi.

Texas emerges as one of the biggest winners under the proposal, getting an extra $35 billion between 2020 and 2026 compared to current law, according to the Avalere study. The KFF study estimates Texas would get about $28 billion more in that time period.

Smaller states that didn’t expand Medicaid will also see more funding: Georgia could see an additional $10 billion between 2020 and 2026, according to the Avalere study. Other big winners are Missouri, Mississippi and Alabama.

Loser — States that spend more on health care

Some states that didn’t expand Medicaid are still losers under the bill.

Most notably, states that didn’t expand Medicaid but still have a lot of people on their insurance marketplaces could see less federal funding under the GOP bill.

Florida, which has an older, poorer population, could stand to lose $4 billion by 2026 under the proposal, according to Avalere. The Kaiser Family Foundation analysis puts that loss closer to $9.7 billion by 2026.

Despite that potential loss of funding, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), one of the biggest critics of ObamaCare, seems generally positive about the new repeal bill.

“I’ve got to see some of the details on how it impacts Florida, but by and large returning power to the states is something I’ve long believed in,” Rubio told McClatchy.

“I don’t think you can design a one-size-fits-all system on virtually anything for a country this size.”

Maine, another high-cost state that didn’t expand Medicaid, could potentially lose between $54 million and $1 billion, according to the KFF and Avalere studies.

While Maine would get additional money for not being a Medicaid expansion state, most of that would be offset by the potential loss of funds under the new funding formula the bill would create for the traditional Medicaid program.

Maine’s Republican Sen. Susan Collins has raised concerns about this.

“I’m concerned about what the effect would be on coverage, on Medicaid spending in my state. On the fundamental changes in Medicaid that would be made without the Senate holding a single hearing … and also what the effect would be on premiums,” she said this week.

Winner — States that spend less on health care

States that have lower health care costs emerge as big winners under the Graham-Cassidy proposal.

This generally benefits southern, Republican strongholds that have lower medical costs and skimpier Medicaid programs that provide fewer benefits. Some states’ programs may not cover dental care, eyeglasses or other benefits. Some programs may also pay their providers less.

“Southern states that have a history of not investing a significant amount in their Medicaid programs, the money will flow to them” because they’ve been spending less, said Jocelyn Guyer, managing director of Manatt Health, a D.C. consulting firm.

The most obvious winner in the short term is Texas. Virginia, another state with limited benefits and strict eligibility, will see an increase of about $3 billion, according to both the Avelere and KFF studies.

Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama will all see billions of dollars more from the federal government than they currently receive by 2026, according to the studies.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.