Opioid crisis sending thousands of children into foster care

The opioid epidemic ravaging states and cities across the country has sent a record number of children into foster and state care systems, taxing limited government resources and testing a system that is already at or near capacity.

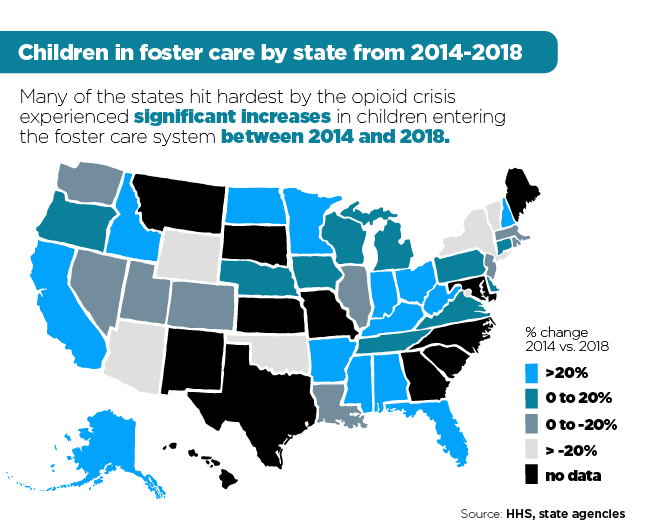

An analysis of foster care systems around the country shows the number of children entering state or foster care rising sharply, especially in states hit hardest by opioid addiction. The children entering state care are younger, and they tend to stay in the system longer, than ever before.

Among states hardest hit by the epidemic, the populations of children in foster or state care has risen by 15 percent to 30 percent in just the last four years, The Hill’s analysis shows. In other states, the number of children referred to child welfare programs has ballooned, even if those kids do not end up in foster care.

“A huge number of children [are] coming into the system now because of parental addiction to opioids that a lot of time has been brought on by pain medication,” said Wendi Turner, executive director of the Ohio Family Care Association.

After a decade of decline, the number of children in foster care across the country began to rise in 2010, just as opioid deaths began to spike. A study from the federal Department of Health and Human Services, released in March, found foster care populations increased by 10 percent between 2012 and 2016, growth the study attributed to the rising number of overdose deaths among parents.

Not every state makes data about foster care systems available. But in the 37 states and the District of Columbia for which data are available, the trend lines are mostly rising.

In West Virginia, home of the highest overdose rates in the nation, the foster population has increased by 42 percent since 2014.

The number of children in state or foster care hit a record low in Massachusetts earlier this decade. Since then, that number has risen by a quarter, and there are now more children in state care than ever before.

In Ohio, the number of children in state custody has grown by 28 percent since 2015. Foster populations are up more than 30 percent in Alabama, Alaska, California, Idaho, Indiana, Minnesota and New Hampshire since 2014.

“Children that are coming into care are staying in care longer because there’s a higher risk of relapse with their parents,” Turner said. “I don’t think our state was prepared for the number of children coming into care so quickly so now we have recruitment efforts going, trying to recruit more parents and also train those parents to handle some of the unique needs of the children.”

The opioid epidemic, which began in rural America, has since spread to more urban areas, where heroin and fentanyl have become more prevalent. The crisis has struck across racial and generational lines.

“[We are] seeing issues in white suburban areas, urban areas, rural areas, crossing gender lines, racial lines, economic disparity,” said Jason Butkowski, a spokesman for New Jersey’s Department of Children and Families. “It seems to be happening all over the state of New Jersey.”

Other drugs have contributed to the increase as well. In states like Nebraska and New Jersey, officials point to widespread methamphetamine use. Substance abuse is a factor in about a third of all cases in which a child is removed from the home, according to a Department of Health and Human Services report.

“It’s not as much an opioid epidemic as an addiction epidemic,” Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey (R) told The Hill.

Historically, foster care systems have been strained at times when new drug crises sweep the nation. B.J. Walker, director of the Illinois Department of Child and Family Services, said her state saw big increases in children needing foster care during the crack cocaine wave in the 1990s and with methamphetamines beginning in the 2000s.

“Substance abuse has always been prevalent within the child welfare system,” said Cathy Utz, deputy secretary of Pennsylvania’s Office of Children, Youth and Families.

With budgets already stretched thin by the Great Recession, states like Illinois, Oklahoma, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Colorado and New Jersey are adopting new approaches to help keep parents and children together, even as parents are receiving treatment for their addictions.

In Massachusetts, the state is investing in residential substance treatment programs that keep families together while a parent gets help. Illinois last year opened a recovery home with space for 18 mothers and their children, and another is in the works.

“Having the children there will be a motivation for parents to stick to their treatment plan,” said Maria Mossaides, who runs Massachusetts’s Office of the Child Advocate. “The hope is, once you’ve finished your treatment and are stable, we can then reintegrate you into your old work and apartment and things that will keep you clean and not create unsafe circumstances for children to be taken away.”

But Massachusetts has also had trouble recruiting and retaining certified foster parents, who must undergo background checks, home inspections and training before they can receive a child. Other states, like Ohio, are racing to recruit more foster parents who could take a child in need.

“If you don’t build the infrastructure up, it creates a whole other problem,” Turner said.

In Arizona, Ducey’s administration partnered with CarePortal, a national organization that works with local churches to help families in need. The number of children in state care has dropped by about 4,000 since 2015, and a backlog of 16,000 uninvestigated cases has been cleared.

But no state has found a workable, long-term solution to the strain caused by the opioid crisis.

“I don’t know that any of us [state agencies] have figured out yet what’s going to really have a long-term impact, or even a short-term impact, on the number of children in the system,” Walker said.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.