Opioid crisis takes personal toll on Washington

Federal and state governments are struggling to respond to the surge in opioid abuse, a devastating phenomenon that is taking an immeasurable toll on the country.

Tens of thousands of families, including those of officials working at the highest levels of government, have seen loved ones struggle with the disease of addiction.

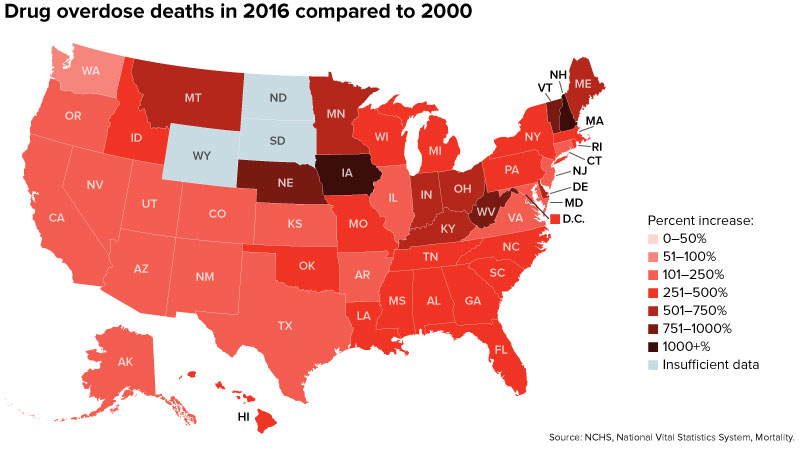

The epidemic has put enormous strain on health care responders, treatment providers and communities across the country, creating a health emergency that shows no signs of abating.

Yet despite the gravity of the problem, there’s a sense from some that the nation isn’t doing enough to stem the crisis.

Congress has approved $6 billion in new spending over the next two years to combat opioid abuse and bolster mental health services, but some say that is a drop in the bucket compared to what’s needed.

“If it were some other illness, we would be throwing exponentially more dollars at this than we are,” said Patrick Kennedy, a former Rhode Island Democratic congressman who’s now a vocal advocate for fighting drug addiction.

“We would be mobilizing significantly more federal resources toward tackling this. We would be marshaling every agency within the federal government to attack this,” said Kennedy, who served on the president’s commission to combat the opioid epidemic last year and has since been critical of the White House’s response to the crisis.

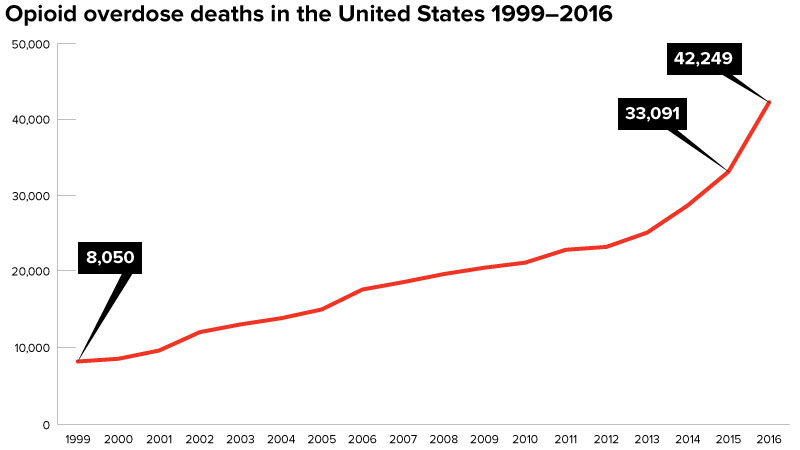

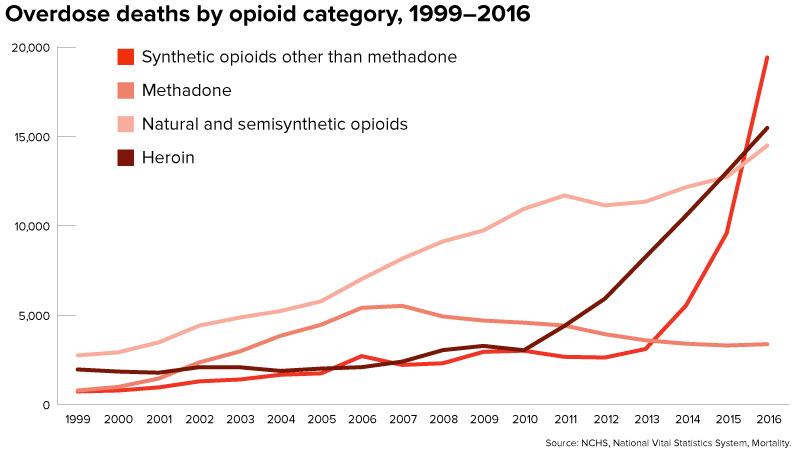

Deaths involving opioids have been rising since 1999. They increased nearly 28 percent from 2015 to 2016, an increase largely driven by a synthetic opioid packing up to 50 times more power than heroin.

An estimated 115 people are dying of an opioid-related overdose every day. When members of Congress return to their districts, they say they hear first-hand how painkillers, heroin and fentanyl are wrecking lives — and that’s resulted in a sea change in attitudes about drug abuse.

The notion that addiction is a disease, rather than a moral failing, is increasingly the consensus.

“My old boss, Michael Botticelli [former President Obama’s drug czar], would say all the time, ‘you can’t hate up close,’ ” said Regina LaBelle, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy’s chief of staff under Obama.

The shift in perspective has resulted in a less punitive response than in the past. In the 1980s, for example, policymakers responded to the crack cocaine epidemic by launching the “war on drugs” and creating mandatory minimum prison sentences for drug offenders.

“If your brother or your sister or your neighbor is dying of a drug overdose, you are less likely to want to have a punitive response, and the difference in what happened today than what happened in the ’80s reflects that,” LaBelle said.

Advocates working on addiction policy say it has also gotten easier to publicize the problem.

More than 15 years ago, when Andrew Kessler first began working in the field, he said advocates “had to fight for every bit of attention we got.”

Kessler, the founder of the behavioral health consulting firm Slingshot Solutions, recalled a presentation he gave in 2013 on addiction advocacy.

“The reason we can’t get a lot of traction is because no member of Congress is going to go home to their districts and say, ‘I’m running on a platform of treating substance abuse and addiction,’ ” Kessler recalled telling the crowd.

“Three years later, in the 2016 election — boom — I was already wrong,” Kessler said.

Kessler attributes the turnaround to the increasing number of opioid overdose deaths, which rose nearly 70 percent between 2013 and 2016.

The response from policymakers is improving, though much more is needed, said Patty McCarthy Metcalf, the executive director of Faces and Voices of Recovery.

“Getting Congress to take this issue up took a lot of work and a lot of advocacy from the grass roots to put pressure on Congress to understand that this didn’t happen overnight, it’s been coming for a while,” she said. “The rate [of opioid-related overdose deaths] has been increasing — we haven’t seen it decreasing, so something is not working.”

Efforts are underway in both chambers to produce opioid legislation, which could be one of the only larger legislative packages to pass before the midterm elections in November.

The House Energy and Commerce Committee has held three legislative hearings on more than 65 separate bills with the goal of getting an opioid package to the House floor before Memorial Day weekend.

On the other side of the Capitol, a bipartisan group of eight senators introduced a follow up to the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, passed in 2016, dubbing the bill “CARA 2.0.” One of the bill’s most controversial provisions is a three-day limit on first-time opioid prescriptions for patients with acute pain.

Earlier this month, the leaders of the Senate Health Committee released a bipartisan discussion draft of an opioid bill, which the panel reviewed at a hearing last week and will mark up April 24.

The Trump administration is also pushing for action.

Declaring “we can be the generation that ends the opioid epidemic,” President Trump made opioids a national public health emergency in late October. But some advocates have expressed frustration with that move, saying it has led to little concrete action.

Last month, Trump released a three-pronged approach to tackle the opioid epidemic, which included some measures popular with public health advocates.

But a portion of Trump’s rhetoric, and a bulk of the subsequent media attention, focused on the inclusion of a controversial provision — mandating that the Department of Justice seek the death penalty for some drug traffickers, when appropriate under current law.

Advocates have said the concept is reminiscent of the war-on-drugs approach that failed in the past.

Instead, they say a focus on prevention, treatment and recovery is what’s needed, as advocates work to stomp out the stigma of addiction. Some progress is being made on that front, advocates say, with more people coming forward to say they have an addiction or lost a loved one to a drug overdose.

“You can see it in the obituaries,” Kennedy said, “literally for the first time ever, you’re seeing on a regular basis people actually acknowledge the true cause of death for people dying of overdoses.”

The second story in this series will publish Tuesday, April 17.

Kaitlin Milliken contributed to this report. Graphics and illustration by Nicole Vas. Video by Tom Pray.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.