Story at a glance

- Evictions can be highly destabilizing to families and communities.

- Virginia has a particularly high rate of evictions, as does the city of Richmond.

- A special exhibit and nonprofit groups are working to reverse the trend.

In Richmond, Va., which is ranked as having the second highest eviction rate in the nation behind North Charleston, S.C., the statistics hit home in a visually compelling exhibit, “Eviction Crisis,” now on display at the city’s main library branch.

“Richmond’s eviction rates are quadruple the national average, with 30 percent of renters each year facing eviction,” says library manger Natalie Draper. “It’s impossible to think that our patrons are not affected directly or indirectly. In fact, we know that many of those we serve are faced with housing insecurity and homelessness,” Draper tells Changing America.

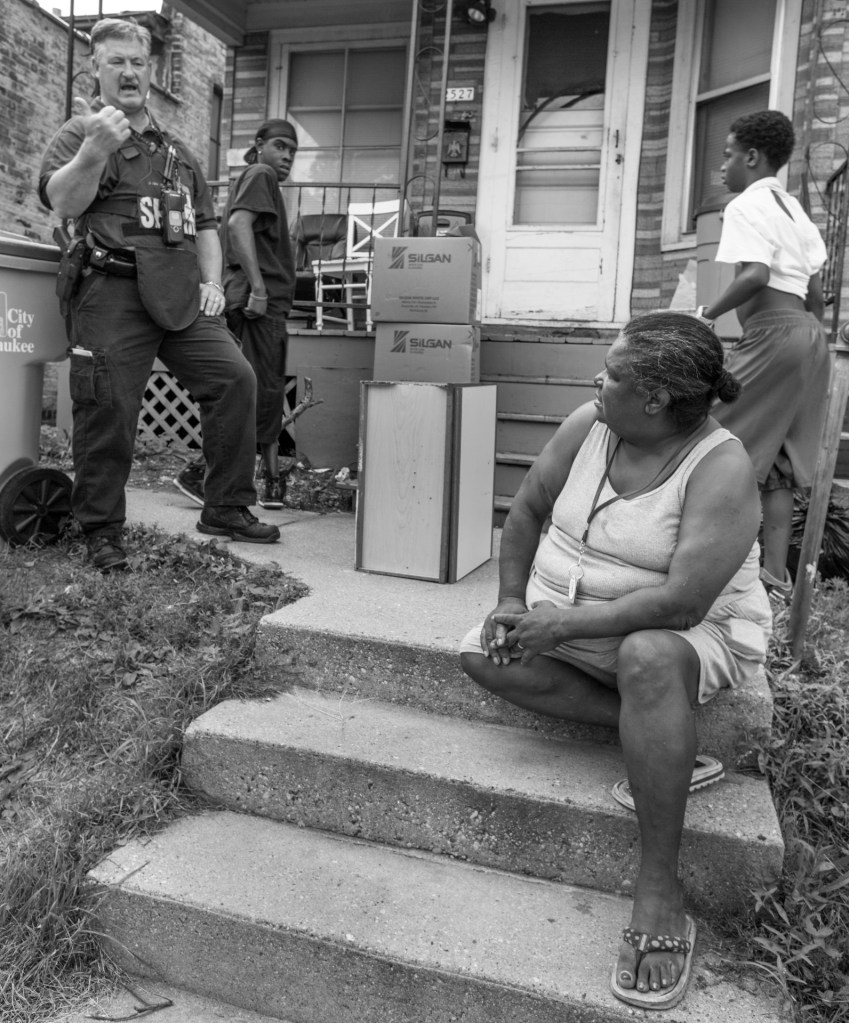

Photo credit: Sally Ryan

Partnering with the nonprofit Housing Opportunities Made Equal of Virginia (HOME) — which created and is presenting the multimedia exhibit — the library hopes to increase awareness of the widespread problem.

HOME is actively working to help reverse the harsh reality; Virginia has five of the top 10 highest eviction rates among large U.S. cities, according to the most recent rankings.

“Virginia has a particularly bad problem with evictions. It stems from very few tenant protections under Virginia law, and a large gap in the availability of affordable housing,” says HOME President and CEO Heather Crislip.

But actions are being taken to change that.

Photo credit: Michael Kienitz

HOME launched the commonwealth’s first Eviction Diversion program in 2019 — “it is designed to be a one-time assist to families that can otherwise afford their housing but have had an emergency that has set them behind in rent,” says Crislip. “We wanted a program that prevented the spiral into poverty that an eviction can cause.”

Key components of the Eviction Diversion program include a financial literacy class, pro bono lawyers to serve as mediators between tenants and landlords, and a payment plan agreement to ensure landlords get back rent while tenants avoid receiving an eviction on their rental history.

The “Eviction Crisis” exhibit at the Richmond main library was inspired by and borrows materials from the National Building Museum’s touring exhibit “Evicted,” which powerfully portrays the struggles of millions of Americans — most of them low-income renters — who face eviction each year.

“Eviction Crisis” debuted at the Governors Housing Conference in Hampton last fall, says HOME Director of Communications Mike Burnette, who designed and built the exhibit along with colleague Kelly Barnum.

It will be at the Richmond Library through end of March. Then it will head to Richmond City Hall in April.

The national exhibition was inspired by sociologist Matthew Desmond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Evicted,” which follows several families struggling with chronic eviction.

Serendipitously, it was students participating in a book program at Virginia Commonwealth University located about a mile from the Richmond library who chose to read “Evicted,” which helped initiate the creation of the HOME “Eviction Crisis” exhibit.

“We were thrilled that they chose ‘Evicted’ by Matt Desmond last year because it is an issue so close to the community we serve,” says Draper.

In fact, even before the exhibit was officially up, several people approached Draper to share their personal experiences with eviction and homelessness.

Photo credit: Michael Kienitz

“Eviction destabilizes communities and families. It is frankly traumatizing,” says Draper. “An eviction, which can happen five days after the rent is due, can often be the catalyst for a cycle of poverty to a family who, without the eviction and all of the cascading expenses that follow, would have been able to stay afloat financially.”

Crislip adds, “In Richmond we’ve found a very high correlation between the census tracts that have high rates of eviction and the elementary schools with high absentee and mobility rates. Kids that move schools and aren’t in the classroom don’t thrive.”

“The community should care because it affects all of us, whether we know it or not,” says Draper.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.