Map shows which coastal U.S. cities are sinking, face greater flood risk

(NEXSTAR) — Those living along the coasts in the U.S. — Atlantic, Pacific, and the Gulf — are no strangers to flooding.

Some in the Northeast saw back-to-back storms earlier this year cause damage to wharfs and sand dunes, and flooding that forced many to evacuate to higher ground. California has been battered with rain — and accompanying flooding — this winter, largely thanks to a strong El Niño weather pattern.

Scientists have long been predicting flooding will only become more common for coastal communities. Last year, Climate Central, an organization of scientists and journalists focused on studying the impacts of climate change, released an interactive map showing which of those communities could be hardest hit by flooding (caused by rising sea levels and typical annual flooding) by 2050.

As if the flooding wasn’t concerning enough, a recently published study shows many coastal communities could all but “disappear” because they’re sinking. In a February blog post, NASA’s Earth Observatory called it a “geologic two-step.”

Land can rise and sink naturally as tectonic plates shift, sediments are compressed, or the Earth’s crust rebounds after being pushed down by ice or sediment, NASA explains. It can also be caused by humans extracting groundwater, building dams, or constructing other infrastructure that blocks sediment flows and interrupts the drying and compacting of peat soils.

Researchers previously determined that in cities like New York, Baltimore, and Norfolk, Virginia, much of the infrastructure sits on land that sank by one to two millimeters annually between 2007 and 2020. In other parts of the East Coast, the sinking (or land subsidence) is happening even more rapidly, the NASA-funded research, published in January, found.

According to the latest research, the coastal sinking, combined with rising sea levels, could put as many as 500,000 people at risk of being affected by damaging flooding by 2050.

The study, published on Wednesday in “Nature,” reviewed satellite measurements of the land around 32 coastal cities in the U.S. and combined them with sea-level rise projections and tide charts, a press release from Virginia Tech explains. Researchers from the university led the study.

“The analogy I have found that is really helpful in helping people understand this change is to think about a sinking boat,” lead author Leonard Ohenhen, a graduate student working with Associate Professor Manoochehr Shirzaei at Virginia Tech’s Earth Observation and Innovation Lab, said in the press release. “Imagine you are in that boat with a steady leak, slowly causing the boat to sink. That leak symbolizes sea-level rise or broadly flooding. What would happen if it also starts raining? Even a minor rainfall or drizzle would cause the boat to sink more quickly than you thought it would. That’s what land subsidence does — even imperceptible millimeter land subsidence exacerbates existing coastal hazards.”

According to their analysis, researchers say 24 of the 32 coastal cities they focused on are sinking more than two millimeters a year. In half of those cities, there are areas sinking faster than global sea levels are rising (about 3.4 millimeters a year).

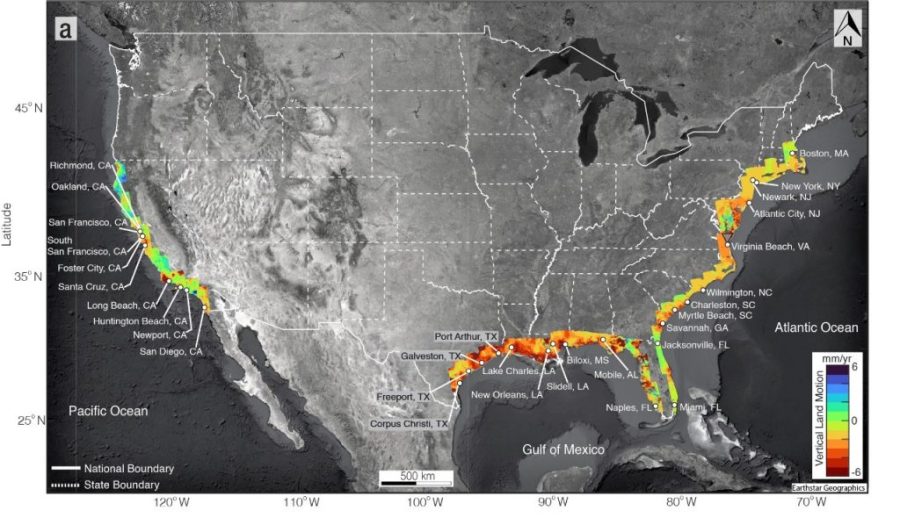

The map below, shared via Virginia Tech, shows the vertical land motion recorded in U.S. coastal communities. Those shaded in oranges and reds are forecasted to sink by as much as six millimeters a year, while those colored green and blue could rise by as much as six millimeters annually. Those that are sinking may find themselves at a greater risk of high-tide flooding, researchers warn.

Researchers determined subsidence is worse along the Atlantic Coast than on the Pacific Coast. Part of that is due to the Laurentide ice sheet. As NASA explains, the massive sheet covered much of the northern portion of the continent. The covered lands were pushed downward, while those not covered by the ice — the Mid-Atlantic area — bulged upward. After the ice sheet melted, that pattern reversed, and the Mid-Atlantic region has been gradually sinking ever since.

In parts of California, the land has actually uplifted rather than sunk as underground aquifers have been refilled, NASA explains. However, other areas have sunk, including Treasure Island, which “has seen subsidence exceeding 10 millimeters per year thanks in part to a landfill on the island,” NASA writes.

It isn’t all bad news. Researchers hope the newest study encourages communities to consider flood control structures, like flood walls, levees, berms, or dikes. Ohenhen said the study found “there is a general unappreciation for flood protection, particularly on the Atlantic coast.”

“And even the levees there often protect less than 10 percent of the city, compared to other cities on the Pacific or Gulf coasts where up to 70 percent is protected,” he explained.

The study also warned that in some communities, like New Orleans and Port Arthur, Texas, the areas with the greatest risk of increased exposure to flooding are occupied by “people of color who are also at an economic disadvantage when compared to the city as a whole.”

A study published in the Journal of Hydrology last summer found that federal estimates about flood risk in the U.S. haven’t kept up with climate change, Nexstar’s The Hill reports.

Nexstar’s Alix Martichoux and The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.