Trump sounds like Pete Wilson — and that scares Calif. GOP

SACRAMENTO — As Gov. Pete Wilson (R) plotted his reelection bid nearly a quarter-century ago, he turned to a secret weapon that would mobilize his core voters: a ballot measure to bar undocumented immigrants from accessing state services like nonemergency healthcare and public schools.

The ballot measure, Proposition 187, passed. Wilson won an unlikely reelection.

{mosads}It was a gambit that would have made Pyrrhus of Epirus, namesake of the Pyrrhic victory — or one that inflicts substantial damage on the winner — blush.

Wilson’s short-term victory came at the long-term expense of the state Republican Party. For more than two decades, Democrats have used Proposition 187 as shorthand with California’s growing Hispanic and Asian communities, one that has marginalized the GOP in the nation’s most-populous state.

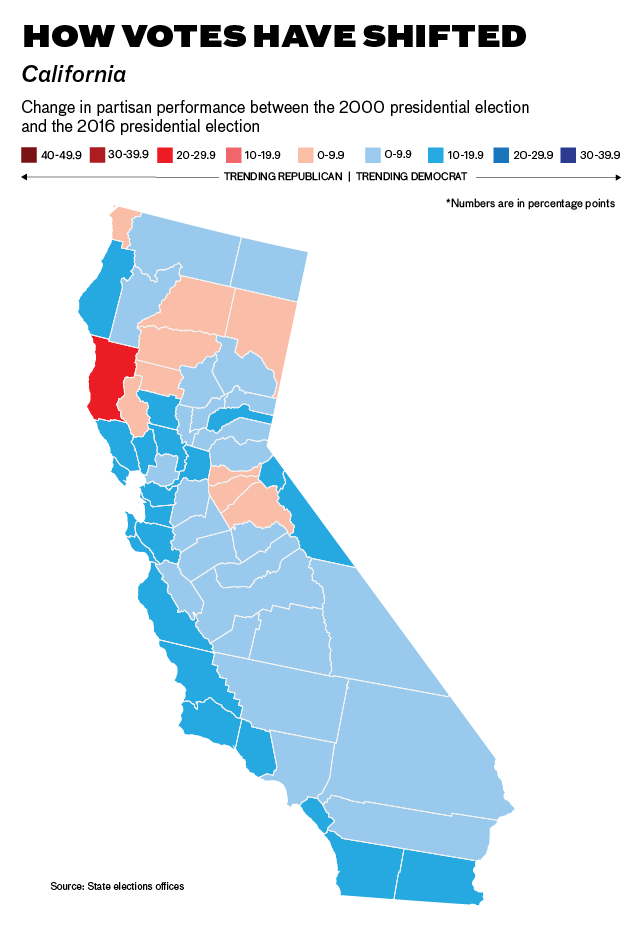

In 2016, another candidate running a Wilson-like campaign with regards to immigrants and Hispanics reached a new nadir. Donald Trump won a smaller share of the vote in California than any GOP presidential nominee candidate since Alf Landon lost to Franklin Roosevelt in 1936.

Now, some Republicans in the state wonder if their party is about to sink further into irrelevancy.

At the same time, some Democrats are mulling just how far to the left their party can afford to govern.

This is the 14th story in The Hill’s Changing America series, in which we examine the demographic and economic trends driving American politics today. California’s story reflects the culmination of the trends that favor Democrats: an increasingly diverse population densely packed in economically vibrant urban cores, one that sees the Republican Party as out of touch at best and actively hostile at worst.

In a state where nearly 40 percent of the population is now Hispanic and another 20 percent are of Asian or African descent, the long legacy of Proposition 187 has driven minorities to the Democratic Party. And Trump pushed more voters away from the state GOP.

“The Democratic Party is increasingly urban, coastal and Latino. And what defines California demographics? Increasingly urban, coastal and Latino,” said Ron Nehring, a former chairman of the California Republican Party and a former spokesman for Sen. Ted Cruz’s (R-Texas) presidential campaign.

California is often cast as a virtual nation apart, a state with an economy so large it can force changes to the global economy. Today, the state generates one-seventh of the nation’s gross domestic product. It generates more economic activity than France. And its new businesses attract nearly half the

venture capital investments made in the entire United States, according to the Martin Prosperity Institute.

The state is so influential that, after Trump announced he was pulling the U.S. out of the Paris climate accord, Gov. Jerry Brown (D) was the first American official to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping — where he signed a deal committing China and California to further reducing carbon emissions.

“California is always going to be the trendsetter,” said Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg (D), a former state Senate president.

The state’s political power is growing, too, at least within the Democratic Party. Even as she lost the presidency, Hillary Clinton broke new ground in California. She took 61.7 percent of the vote there, and she beat Trump by 4.3 million votes. Nationwide, Clinton won the popular vote by nearly 2.9 million votes.

Clinton’s margins are a microcosm of what works for Democratic candidates around the country. The 33 counties she won are more diverse, more populous and more prosperous than the 25 counties Trump won: Ninety-four percent of all personal income earned in the state of California was earned in counties Clinton carried, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Of the 33 counties Clinton carried, all but two added population between 2010 and 2015. Of the 25 counties Trump won, 15 lost population over that span.

Most observers say California’s leftward shift is a result of both changing demographics and the harsh rhetoric Trump employed — language that worked for Wilson but that now hurts California Republicans. Wilson, now 83, told the Los Angeles Times earlier this year he has no regrets about pushing Proposition 187.

“California voters are explicitly reacting against the direction of the modern Republican Party,” said Thad Kousser, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego. “So many of these California districts now have this critical mass of voters who are immigrants themselves, or first- or second-generation immigrants, and that’s not where Donald Trump plays.”

Clinton even made inroads in what has long been deeply red territory: She won Riverside County, in the heart of the Inland Empire. She won Nevada County, once the epicenter of the California Gold Rush. And, stunningly, she won Orange County, once the core of California conservatism.

“Clinton won in Orange County because they didn’t want Trump,” said state Sen. John Moorlach (R), who represents the area. “The Republicans just haven’t provided an exciting product.”

As Clinton ran the table around the state, Democrats ascended to new heights down the ballot as well. The party picked up a supermajority in both the state Senate and the state Assembly. State Republicans were so dismally organized that the runoff for an open U.S. Senate seat featured two Democratic candidates.

Nearly 20 percent of Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives hail from California. No single state has ever held a higher percentage of one party’s seats in Congress. And California Democrats believe they have more opportunities to win back seats: Clinton beat Trump in districts held by GOP Reps. Jeff Denham, David Valadao, Steve Knight, Ed Royce, Mimi Walters, Dana Rohrabacher and Darrell Issa — all districts with heavy minority populations.

But some Democrats are wary of becoming victims of their own success. The major fights happening in the state legislature today are rarely between the two parties; rather, they are between the liberal and more moderate factions of the Democratic Party.

One wing, loyal to progressive Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), is advocating for a single-payer healthcare system; the other is loyal less to Clinton than to Brown, a social liberal but fiscal centrist.

“You have very similar sides lining up as you did in the Democratic primary,” said state Sen. Mike McGuire (D). “What is happening at the national level has spilled over here.”

So far, what might be called the Brown-Clinton faction has notched virtually all of the victories. The single-payer proposal was shelved by state Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D), who worried about a lack of a funding mechanism. A contentious race for state party chairman was won by a longtime party insider who narrowly held off a Sanders-backed insurgent, though the runner-up claimed there were voting irregularities. And a cap-and-trade proposal Brown backed, seen as too conservative by some in the environmental community, won approval from the legislature.

But state Democrats see the fault lines emerging within their own party.

“There is a progressive end in our party pushing to upend the status quo,” said state Sen. Toni Atkins (D), a former state Assembly Speaker.

The demographic changes that have delivered California so completely into Democratic arms are showing up in other states, too. Already, Hispanic voters have moved states like Nevada and New Mexico out of the swing category and safely into the Democratic column. Similar changes are taking place, albeit more slowly, in states like Arizona, Florida, Texas and Georgia.

Those states will not become the hotbed of liberalism that California represents — but the Golden State offers a worrying harbinger for the GOP.

“There’s a tendency to write off California as just the odd person out,” Nehring said. “But it’s not. It is a glimpse into the future, and it is a warning to Republicans nationally [about] what is in store unless we take that into account.”

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.