Steel yourself: Trade conflicts could be just the beginning

The U.S is becoming more belligerent on imports.

The first president of the United States, George Washington, influenced as he was by Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations,” was a great advocate of free trade. Smith’s passion for unfettered commerce oozes out of Washington.

In his farewell address, Washington said, ”Even our commercial policy should hold an equal and impartial hand: neither seeking nor granting exclusive favors or preferences.”

{mosads}It is somewhat ironic therefore that, on the day we celebrated Washington’s birthday last month, the concept of free trade was being disregarded in the city named after him.

Wilbur Ross, the U.S commerce secretary, advised the White House on Presidents’ Day weekend that a tariff on steel and aluminum imports would be justifiable on national security grounds. President Trump has now said that he plans to use this “big sledgehammer” which allows him to impose tariffs without congressional approval.

This particular national security angle dates back to when there was concern over whether the U.S would have available steel to build war machinery — like tanks.

The tariffs have yet to be implemented, but the international reaction has been swift. Even before the president formally announced the new policy, the Financial Times reported, “China threatens to retaliate against U.S metals tariffs.”

Now the BBC declares, “European Union gears up for trade war.” This is dramatic stuff. But, as a scholar of social mood, I do not ask “What is the news?” Rather, I ask, “Why is this news happening now?”

Robert Prechter’s socionomic theory proposes that global tensions over trade are manifestations of a negative trend in social mood. Until February, the overall barometer of global social mood, the world stock market index, had been on a tear in nominal terms.

Stock markets have fallen since then, reflecting a shift in social mood toward the negative. Furthermore, a closer look at social psychology regarding international trade in particular reveals an even more interesting picture.

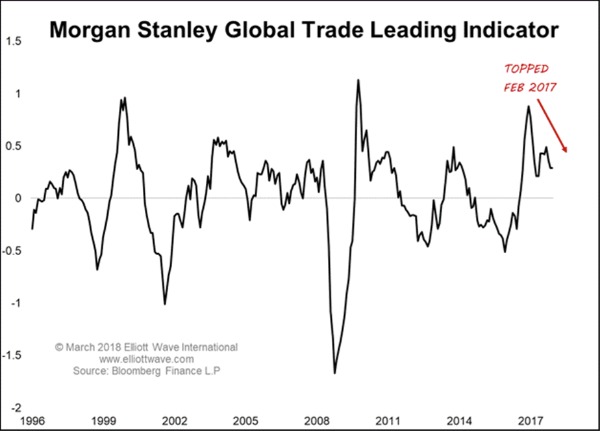

The chart below shows the Morgan Stanley Global Trade Leading Indicator.

This diffusion index (a measure of rate-of-change, rather than value) is a proxy for global trade conditions and is calculated using equally-weighted readings of:

- Brent crude oil,

- the Reuters/Jefferies Commodity Research Bureau (CRB) index,

- the Baltic Dry (shipping) index,

- U.S. dollar broad trade-weighted exchange rate,

- the U.S Institute of Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing index and

- the German Information and Forschung (research) — Ifo — Business Expectations index.

The graph shows that global trade conditions, using this aggregated measurement, actually have been deteriorating since February 2017. Therefore, a ratcheting up in trade war rhetoric is consistent with the downtrend.

If global trade were to continue to head south, there’s no doubt that commentators would give the Trump tariffs a hefty amount of the blame. But the tariffs cannot be the cause of a trend that was under way for more than a year prior to their announcement.

Financial pundits are already blaming the tariffs for the most recent stock market sell-off, when in fact the market’s gyrations and the tensions over trade are both symptoms of the darkening mood rather than its cause. When our psychology changes, so does our behavior.

Anyone who has read history will know that the negative mood trend responsible for trade wars has often carried over into much more serious conflict. The world is not there yet, but mood appears to be transitioning in that direction.

Murray Gunn is the head of global research at Elliott Wave International, a firm specializing in technical analysis of financial markets worldwide. He formerly was the head of technical analysis for HSBC Bank. He is also a contributing author to the recent book, “Socionomic Studies of Society and Culture.”

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.