America’s health care paradox: We need smarter spending, not more

It’s an old American story: We pay more for health care than any other country on the planet, yet outcomes lag those of other developed nations. This embarrassing fact keeps us obsessed with cutting health care costs, presumably so that lower costs better reflect the lower value of our health care investment.

But there is another way to achieve value, and that is by changing how we spend our $4.3 trillion in annual health expenditures.

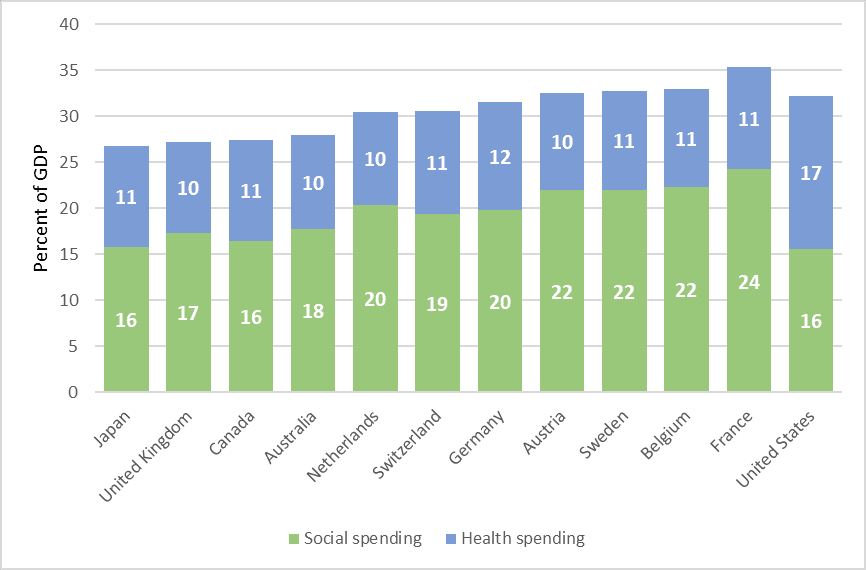

Other developed countries have figured this out, and new data compiled by the KFF-Peterson Health System Tracker provide a timely reminder of the urgency to change our spending patterns by investing in non-medical drivers, or social determinants, of health.

Compared to spending patterns for the same countries based on earlier data, the new data show that from 2011 to 2019, although the U.S. increased its investment in social spending, it continued to overinvest in health compared to social spending, while comparable countries continued to do the opposite. And over that same period of time, U.S. health outcomes continued to fall behind those of comparable countries, and in some cases, the gap grew larger.

Our analysis of Organization for Economic Cooperation (OECD) data showed that from 2011-19, life expectancy in the comparable countries increased by one year on average, while U.S. life expectancy remained flat, still 3.8 years lower than the average of the other countries. And while both the comparable countries and the U.S. reduced their infant mortality rates slightly over this eight-year period, the U.S.’s 5.6 deaths per 1,000 births is still nearly twice that of comparable countries (3.3 per 1,000 births).

In the case of maternal mortality, our analysis of UNICEF maternal mortality data shows the rate in every one of these comparable countries declined (with an average decline of 14.3 percent) from 2011 to 2019, while the U.S. rate increased by 30.1 percent. Notwithstanding our outsized health care spending, the U.S. is by far the most lethal country for new mothers, with a maternal mortality rate in 2019 of 19.9 per 100,000, while comparable countries had a fraction of as many deaths (6.1 per 100,000).

Why do we keep doing this?

For decades, health professionals have known that social, environmental, economic and behavioral factors are more determinative of health outcomes than medical care. One of us began studying spending patterns among developed countries more than a decade ago, identifying the paradox of the U.S. spending more on health than other countries without having the outcomes to justify the spending. Similar analyses were made by others using 2009 data and 2011 data, finding the same patterns in spending and outcomes. Now, data through 2019 confirms that as the U.S. continues to neglect social spending on health, its outcomes continue to lag.

We can change our spending trajectory. The seminal work of Harvard’s Michael Porter and Elizabeth Teisberg on value-based care, through the creation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid’s (CMS) Innovation Center as a key part of the Affordable Care Act, we’ve understood the mechanisms for moving dollars upstream by shifting payments away from the traditional fee-for-service model to health outcome-oriented payment models.

The Innovation Center has deployed more than 20 models that incorporate non-medical drivers into the health care delivery system. The growth in popularity of Medicare Advantage plans is due in part to the inclusion of non-medical benefits such as carpet cleaning for asthmatics and nutrition and exercise programs for diabetics. CMS is approving Medicaid waivers with significant investments in non-medical drivers such as food and housing and encouraging states to use “in lieu of services” authorities to support non-medical investments. Hospitals are increasingly being urged to invest in improving community health outcomes.

While the U.S. historically has been less inclined to make the kinds of social investments in children and families as other developed countries, we have an opportunity to redirect our outsized, underperforming health dollars upstream to improve health outcomes — a bipartisan goal, as evidenced by the growth of such programs through Republican and Democratic administrations. And because the federal government is the largest single payer of health care costs, these programs can have significant influence over the entire health care system.

We must take advantage of this momentum to push more dollars upstream to improve U.S. health outcomes. If we’re going to spend nearly 20 percent of GDP on health, we deserve better value.

Elena Marks, JD, MPH, is a senior fellow in Health Policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. Elizabeth Bradley, Ph.D., is the president of Vassar College and the co-author of “The American Health Care Paradox: Why Spending More is Getting us Less” (with Taylor, L. 2013 Public Affairs).

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.