How runaway disability compensation is straining Veterans Affairs

As we celebrate Veterans Day this year during the 50th anniversary of America’s all-volunteer force, growing concerns about the federal debt, a looming budget impasse and a crisis in military recruiting prompt us to call attention to the causes and consequences of the immense growth in the budget for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs in recent years.

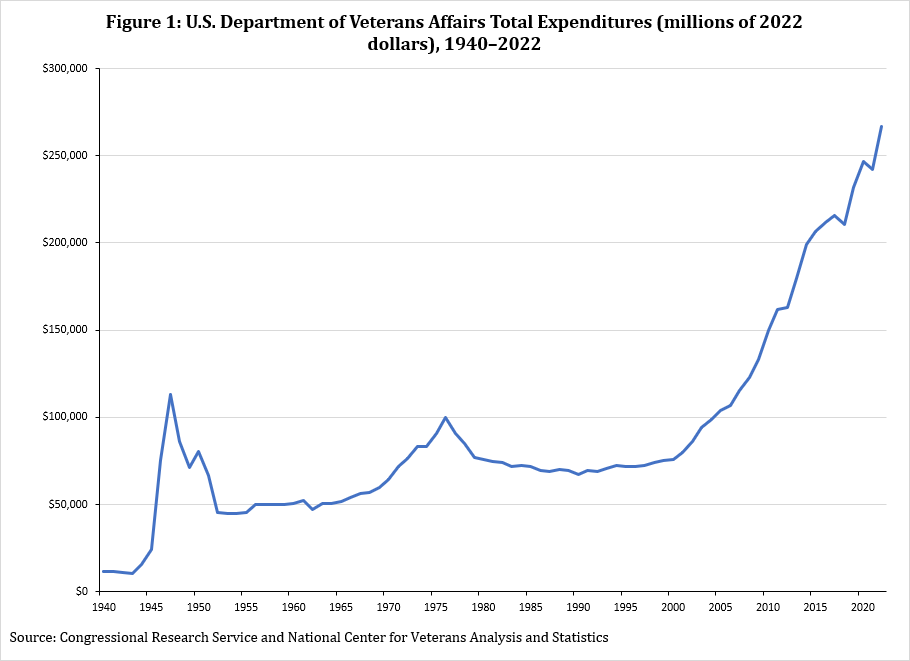

From 2000 to 2022, the overall VA budget grew from $76 billion to $267 billion (in 2022 $) despite a 30 percent decline (from 26.4 million to 18.4 million) in the veteran population over the same period. As a result, annual spending by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs per veteran has quintupled, from $2,900 to $14,500. Some of this growth has been driven by an aging veteran population, rising healthcare prices and much-needed improvements to VA healthcare facilities

But the biggest contributor to the VA’s steadily expanding budget has been the unprecedented increase in veterans’ enrollment in disability compensation, a VA program designed to compensate America’s veterans for injuries incurred or aggravated during their military service. The share of veterans receiving disability compensation benefits is increasing rapidly and is at an all-time high. Between 1954 and 2000, the share of veterans receiving disability compensation was very stable, fluctuating between 8 percent and 10 percent. Today, nearly 30 percent of the country’s 18.5 million veterans receive it.

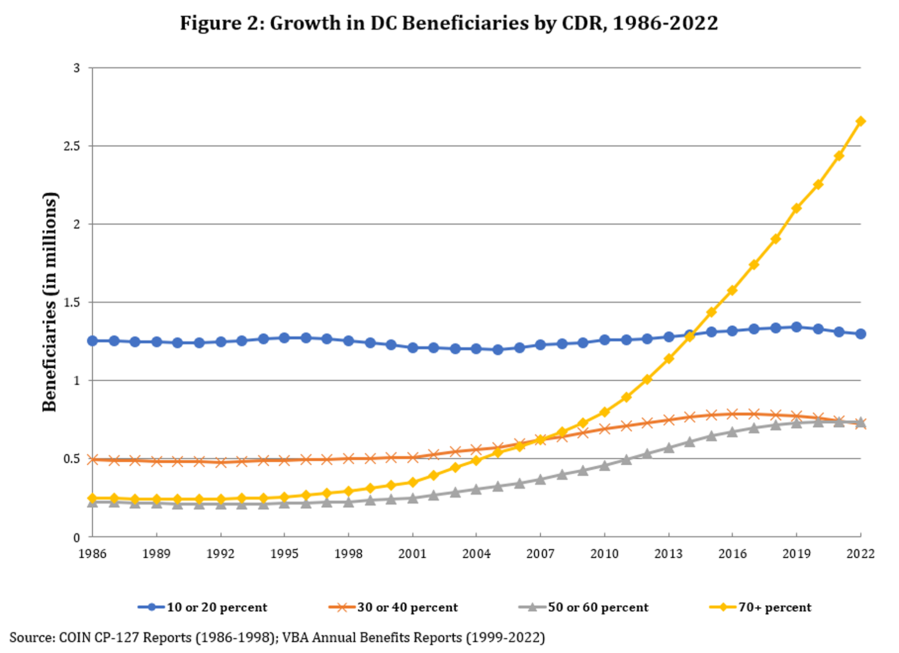

Additionally, the average annual payment to veterans receiving disability has increased substantially, from about $12,000 in 2000 to $21,000 today. This growth has been driven by a shift to much higher disability ratings since payments are higher for those who are found to be more disabled.

From 2000 to 2022, the number of disability compensation recipients with a rating of 70 percent or more increased by 7-fold (from 0.34 million to 2.66 million) while the number with a rating of just 10 or 20 percent hardly changed (from 1.23 million to 1.30 million). This rating system used by the VA encourages disability compensation recipients to apply for increases in their ratings and may discourage some from improving their health.

With total annual disability compensation expenditures increasing from $28 billion to $112 billion, VA spending on the program is now 83 percent as large as for Social Security Disability Insurance, the largest federal disability program that insures 10 times as many adults. Moreover, since veterans who receive disability compensation benefits have increased eligibility for the VA’s health care services, the program’s rise in enrollment has simultaneously contributed to substantial increases in health care spending by the VA (the other main category of the VA’s budget).

In comparison, annual VA spending on education benefits such as the GI Bill is just $10 billion, and annual spending on veteran readiness and employment, a program designed to help veterans with service-connected disabilities obtain stable and suitable employment, is only $1.5 billion.

The primary driver of the growth in disability compensation enrollment has been a series of regulatory and policy changes over the past two decades (including most recently the 2022 PACT Act) that have made it steadily easier for veterans to apply for and qualify for disability benefits for a broader set of medical conditions. As a result of these changes, nearly 40 percent of veterans who served in 1990 or later receive disability compensation benefits.

While one might attribute these high rates of disability compensation receipt to improved battlefield medicine and the long-term effects of combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, recent research suggests otherwise.

Veterans who enlisted since 2010 have some of the highest rates of disability compensation enrollment even though they were significantly less likely to deploy and faced a substantially lower risk of injury while deployed — only 1 percent of Army service members who enlisted between 2010 and 2015 were wounded in combat.

Considering how much easier it has become to qualify for disability benefits, it is perhaps unsurprising that 5,000 pilots who passed their Federal Aviation Administration physicals are now under investigation for receiving veterans’ disability benefits for conditions that should disqualify them from the cockpit.

So why is this a problem? Extra money from the disability compensation program may improve some veterans’ economic well-being. However, previous research by both of us and with other co-authors has demonstrated that disability compensation has significantly lowered veterans’ employment.

The program’s impact on health is also mixed. Despite the increase in disability compensation enrollment and corresponding growth in VA expenditures, veterans’ mental health, measured by suicide rates, has deteriorated relative to non-veterans of the same age and gender, another trend that is not explained by combat deployments.

While some recent studies find evidence that disability compensation improves engagement in preventive care and may decrease hospitalizations among Vietnam-era veterans with diabetes, there is little evidence that it reduces veterans’ mortality or improves other measurable health outcomes.

And if disability compensation’s growth is attributed to deteriorations in veterans’ health rather than to policies that make it easier for veterans to qualify for disability, then it may inadvertently feed a “broken veteran narrative” that contributes to the military’s worst recruiting crisis since the advent of the all-volunteer force.

In fact, recent surveys cite concerns about physical injury and psychological distress as the top two reasons youth do not consider joining the military. Unfortunately, such narratives crowd out other research which finds that Army service increases average earnings in the 19 years after enlisting by over $4,000, with Black service members and those from disadvantaged backgrounds experiencing even larger gains.

If VA spending per veteran had remained the same in inflation-adjusted terms since 2000 — its total budget would have been about $60 billion in 2022 rather than $267 billion (and growing rapidly). We are not arguing for cuts to the VA’s budget. On the contrary, broad, bipartisan support for veterans, including generous spending for veterans’ healthcare, education benefits and other support services, may help explain why military service increases earnings and why combat deployments, though they increase soldiers’ immediate risk of death and injury, have few harmful long-term effects on well-being.

But it’s time to ask if an increasingly generous disability compensation program that has significantly reduced employment among our veterans and bears no resemblance to the program that existed throughout the latter half of the 20th century is the best way to reward and honor America’s veterans while also inspiring today’s young adults to serve their country in the armed forces.

Kyle Greenberg is an associate professor of economics in West Point’s Department of Social Sciences. Mark Duggan is the Trione director of the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and the Wayne and Jodi Cooperman professor of economics at Stanford University.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.